An Unearthly Child

It's 23rd November 1963. Gerry and the Pacemakers' "You'll Never Walk Alone" is at number one – oh wait, TARDIS Eruditorum is already a thing? This requires a rethink. Whatever. I'll rip off Toby Hadoke and Rob Shearman instead...

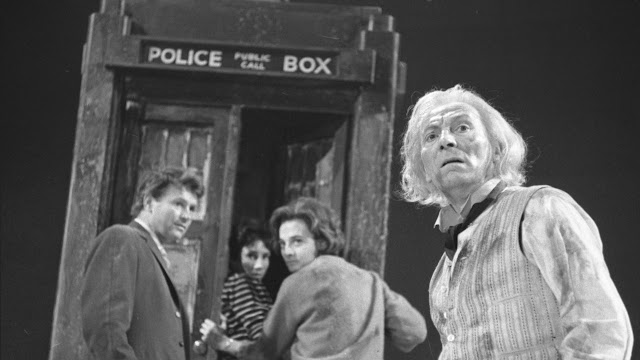

An Unearthly Child, Episode

One: An Unearthly Child

What

else is there to say? We all know this is one of the best first episodes of any

television series. Which is a difficult thing to achieve: so many long running

series’ early episodes don’t quite

feel like the programme they’ll eventually become – and it goes without saying

that Doctor Who never stays as one thing for too long. But for an episode

produced by the youngest and only woman producer at the BBC, directed by the

BBC’s youngest and only BAME director, on a shoestring budget, and recorded on

old cameras in the BBC’s worst studio space, it’s extremely confident. And

behind the black and white videotape, it still feels fresh. Those working on

Doctor Who in 1963 might have thought they had a hit on their hands, but

no one could have known they were at the beginning of a television legend. And

yet the whole episode acts like it’s the start of a legend: as Elizabeth

Sandifer says on the aforementioned TARDIS

Eruditorum when we first see the police box, the “mysterious, haunting theme music gives way to an iconic shot. Never mind

that the shot cannot possibly be read as iconic in this original context –

everything about the camerawork and the music tells us it is iconic”. And it

continues like that the whole way through: as a mystery story, every dramatic

beat lands; regarding the characters, although they’ll develop as the series

progresses, we know exactly who each of them is already; and it’s so pacey. In

nearly every respect, it’s a triumph.

Something

I imagine I’ll discuss a lot in these blogs is how Doctor Who (along with, say,

David Bowie or Kate Bush in music) brings the strange into popular culture. And

it’s here from the first moment of the first episode: that unsettling and so

utterly televisual howlround effect, perfectly paired with Delia Derbyshire’s

electronic arrangement of the theme tune (a piece of music I’ve undoubtedly

heard more than any other, and still never tire of) – it already looks and

sounds like nothing else on early

1960s television. So, we open with police box from which emanates a weird

pulsating noise. And it’s a police box that turns out to be a time machine. A

police box that ends up on prehistoric Earth. Postmodernism on television

begins here, folks.

But

this strangeness is written into the script itself: the whole episode is set up

to begin within the ordinary confines of 1960s drama and then destroy all of

the audience’s expectations. Although the first half of the episode obviously

doesn’t have the same political or emotional heft as a Cathy Come Home or A Taste of

Honey, it’s recognizably social realism: two schoolteachers in an inner

London comprehensive school are worried about one of their pupils and decide to

investigate (it’s surprising how heavily the subtext leans into Susan being

abused here, especially when you remember this aired at 5:15pm). They see her

go into a junkyard, and rather than finding her, they find a police box, and an

irascible old man. He mocks them and avoids their questions. They hear Susan’s

voice come from inside the police box, force their way through, and in the

smash cut that changes everything, we’ve gone from a dingy, dark junkyard to a

gleaming white, 60s futurist time machine. And then the action slows down, and

the camera pans across the whole TARDIS console room, forcing us to take it in.

The programme – the TARDIS itself – is screaming out at us: ‘whatever this is

going to be, it’s going to be like nothing you’ve ever seen before’.

This

isn’t really social realism for kids, this isn’t even Quatermass for kids: already it’s a madman in a box, with no idea

where he’s going. In 25 minutes, we jump from social realism to an alien

abduction story via an entering into Narnia moment, and next week, it’s going

to change again. As the first instalment in a series that can, in principle, go

anywhere and do anything; that steals from, subverts, and synthesizes genres;

that revels in just being plain weird

– this is as strong a start as we could have hoped for. Quite what the

programme will become is still up for question – the nuances are still being

drawn – but 25 minutes in, as the theme music fades in again and the image of a

police box in a desert fades out, we’re left assured that television’s never

going to quite be the same again.

An Unearthly Child, Episode

Two: The Cave of Skulls

Let’s

begin with the fan consensus: ‘An Unearthly Child’ is said to have a brilliant

first episode, only to then be let down by three consequent episodes in which

some cavemen bicker about fire, and the TARDIS crew continually get captured,

escape, and recaptured. There’s something true about this: where Episode One

had a much longer process of preparation, and indeed a full remount to get it

exactly right, and where Episode One pushes far beyond the perceived

limitations of 1960s television, Episode Two is much more in line with the

quickly and cheaply produced theatre-like television of 1963 and all the worse

for it. Furthermore, Episode Two is the least compelling of the four:

it’s the one in which the TARDIS crew are most sidelined while the Tribe of Gum

are introduced, there’s a really long scene which takes up far too much of the

episode where the tribe are bickering,

and after an extremely tightly plotted first episode, this somewhat meanders

around in search of a purpose. But I want to keep this blog as positive as

possible, because Episode Two, in a way, has an equally important function to

perform alongside the first: that is, where Episode One pushes the boundaries

of our expectations of what this ‘Doctor Who’ thing is going to be, Episode Two

is there to show us how far Doctor Who can go – literally. We’ve gone from

contemporary London to the dawn of human civilization and the discovery of

fire. In human terms, we’ve gone back as far as we can go. And for all that doing

a caveman story is hard to pull off, having them bicker is a damn sight better

than having them grunt. And even if I think the ‘Za and Kal power struggle is a

metaphor for politics writ large’ reading is a slight overinterpretation, certainly it’s the case that in and

amongst all the arguing, we see the generational divides within the tribe and

the tying of power to masculinity. All the themes are there, but quite what

this story is trying to say is much less clear.

The

cliffhanger’s good though: the TARDIS crew have been captured by the tribe and

imprisoned in a cave full of skulls that have been split open that the camera

won’t stop lingering on. Wonderfully sinister.

Also

of note: the ‘Doctor who?’ joke happens here for the first time. Actually, it happens

twice. Did Steven Moffat travel back in time and write this?

An Unearthly Child, Episode

Three: The Forest of Fear

Again,

there are a couple of things the fans always point out about this episode, so

let’s get them out of the way first: (1) the massive inconsistency in the

Doctor’s character here (when we know the sort of character he’ll become) when,

in desperation, he tries to stone Za; and (2) the apparent sexism of Barbara’s

breakdown. There are a couple of things to say, re (1): it is shocking to us

now, but the Doctor is on a character journey in these early few stories, and

by the time we get to Marco Polo, Hartnell’s Doctor will be rather sweet and

almost cuddly. In a way, the Doctor becomes the Doctor because he meets Ian and

Barbara: if Capaldi is going to ask ‘am I a good man?’ in 2014, the reason our

response is ‘obviously, yes’ is in large part down to Ian and Barbara’s

influence. Looking back now, the Doctor isn’t quite the Doctor yet – and if Matt Smith was so good at

playing an ancient man in a young man’s body, Hartnell is exactly the opposite

here. For all Hartnell’s Doctor looks old, he’s a young man here: scared, and

with no idea what he’s going to do next.

But

in some moments, the Doctor we know does begin to shine through, and Hartnell’s

delivery of the lines, “Fear makes companions of us all […] Fear is with all of

us and always will be. Just like that other sensation that lives with it […]

Hope”, is just wonderful.

Regarding

(2): maybe there is something sexist about the fact Coburn chooses to have

Barbara break down rather than Ian, but as someone who’s been forced into an

alien environment against her will, Barbara’s response nevertheless feels true.

And she’s on a character journey too: by the time we get to The Aztecs – and almost

certainly before – she’s the strongest member of the crew. (Plus, in so many

ways, human prehistory here feels more alien than the succession of futuristic

stories Doctor Who is going to start doing soon – it’s one of the story’s real

strengths).

Otherwise,

this is a marked improvement on Episode Two: now that the tribe has been

introduced, this episode can spend more time with the Doctor, et al. – and the

character interaction between the TARDIS crew as they escape the cave, which

takes up a decent chunk of the episode, is by far the episode’s highlight and

satisfyingly builds on the character notes introduced in Episode One.

But

for someone who has only seen the new series, they might be quite surprised by

how dark Doctor Who is in its early days: having your lead character attempt to

bash someone’s head in with a rock is hardly ordinary children’s TV

fare, and the script goes out of its way to make us sympathize with Ian and

Barbara over the Doctor. But as the episode’s title and the Doctor’s speech

make apparent, this episode’s theme is something Doctor Who is going to return

to time and time again: fear. Everyone in this episode acts out of fear: from

the TARDIS crew’s escape by means of the Old Mother freeing their bonds (they’re

afraid of the tribe, whereas she’s afraid of fire (and isn’t Eileen Way

brilliant?)); to the different ways the crew interact with one another; and Za

and Kal’s attempts to undercut one another for power over the tribe. We see

Barbara’s compassion when she insists on helping Za when he’s wounded even

though it entirely scuppers their chances at escaping, but even then someone

acting rashly is just around the corner. If fear lives with hope, then we’re in

need of some hope right now.

An Unearthly Child, Episode

Four: The Firemaker

So

much for hope. This is a bleak episode. Fear is still moving everyone along.

There isn’t even a real plot resolution: the TARDIS crew, by the skin of their

teeth, simply escape. But that’s by no means a bad thing: Doctor Who is never

really going to be this (quote unquote) ‘realist’ again. Not realist in the

sense that this is an accurate representation of prehistoric humanity – clearly

it isn’t – but it’s visceral in a way

the series never quite attempts again.

And

there are some moments of light. Za and Hur’s discussion (which can only be

described as ‘political’), of the importance of the unity of the tribe over the

individual in order to survive, something they learn from Ian and Barbara’s

compassion, is gorgeously written and performed – and the sequence where the

TARDIS team finally do escape (which is on film!), for all that it’s obviously

just the actors being hit by a stagehand with some tree branches in close-up

while they run on the spot, nevertheless just works (or it does for me, anyway); there’s a reason the director,

Waris Hussein, is going to win an Emmy in 15 years’ time.

But

the TARDIS team do escape, and Ian and Barbara still haven’t got home yet.

There’s a strange forest on the TARDIS scanner that looks scorched from some

sort of disaster. At any rate, we definitely aren’t on Earth anymore. Let’s hope the

planet really is dead.

An Unearthly Child Episode

Ratings:

Episode

1: 10/10

Episode

2: 7/10

Episode

3: 8/10

Episode

4: 8/10

Mean

Average: 8.25/10

Comments

Post a Comment